Los movimientos en torno a la competición entre grandes potencias protagonizada por los EE. UU. y la República Popular de China determinarán la arquitectura internacional de seguridad durante las próximas décadas. De todas las regiones en las que ambos contendientes se juegan su liderazgo, quizá la más importante sea la Indo-Pacífica. El Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad, de consolidarse, podría otorgar a los EE. UU. una posición de ventaja que Pekín pretende evitar a toda costa.

Sara Álvarez Quintáns

Como iniciativa de asociación estratégica, el Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad, o simplemente “la Cuadrilateral”, nació al amparo de Estados Unidos y Japón con el objetivo de contrarrestar la creciente influencia china en el Pacífico occidental. Mediante la construcción de una red de alianzas regionales, las cuales incluían India y Australia, se pretendió promover la cooperación militar entre estos países.

Sin embargo, la iniciativa sufrió numerosos altibajos a lo largo de su corta pero intensa historia. Finalmente, tras la retirada de Australia e India, pareció que el futuro de la Cuadrilateral tenía los días contados. Ya poco, o nada, se hablaba de esta idea.

En los últimos tiempos, no obstante, las cada vez más frecuentes actuaciones de China en el contexto regional del Indo-Pacífico y la creciente inestabilidad en la región han hecho que las percepciones de seguridad por parte de los antiguos miembros sean redefinidas. Ahora, el Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad podría encontrar un escenario propicio para salir adelante, a diferencia de lo sucedido en el pasado.

¿Qué es el Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad?

El Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad se pone en marcha como una propuesta de asociación estratégica (strategic partnership), muy diferente a los mecanismos de las alianzas más tradicionales. En la asociación estratégica, las partes no son estrictamente aliadas, pero se asume que comparten una visión sobre un desafío en concreto, y para hacer frente al mismo ponen sus propios recursos a disposición de los demás miembros de dicha asociación.

Esto forma parte de las nuevas tendencias en materia de seguridad y alianzas, que algunos autores denominan coalitions of the willing. Estas nuevas fórmulas, que se podrían denominar “informales”, permiten una considerable flexibilidad a la hora de dar forma a la asociación. Desde escoger en qué campos se quiere colaborar, hasta los grados en que se pretende hacerlo, sin descartar que se produzcan cambios en las percepciones e implicación de las partes.

Las ventajas más evidentes que ofrece este sistema son la rapidez y la utilidad. El marcado dinamismo de las interacciones entre las partes implicadas permite que se creen grupos concretos para tratar problemáticas concretas sobre las que se ha acordado una línea de actuación con anterioridad. Con este proceso se eliminan ciertos obstáculos que podrían retrasar, o incluso desestimar, la actuación. Es, por consiguiente, un sistema basado en la obtención de resultados mediante interacciones dinámicas inmediatas.

La segunda Cuadrilateral (Quad II) incorpora el enigma definicional a la naturaleza de la propia asociación. Si en su nacimiento ya había respondido a términos un tanto laxos, tal y como se viene explicando, su reaparición no parece implicar, por el momento, una mayor concreción a sus líneas definitorias. Por el contrario, todavía está por verse si la iniciativa adopta la forma de una coalición informal cuyo objetivo principal sería luchar contra la influencia china en la región del Indo-Pacífico, o si, por otro lado, continúa siendo una fórmula altamente flexible y adaptativa, lo que le permitiría responder a distintos objetivos. Euan Graham[1], del Lowy Institute en Australia, argumenta que esta última es una táctica que permite delegar el peso de la cuestión sobre Pequín en lugar de los propios miembros de la Cuadrilateral: dependiendo de la intensidad de las actuaciones de China, la iniciativa podría funcionar más como un instrumento diplomático de disuasión, según lo requiriese la situación.

Sin embargo, esta ambigüedad también puede llegar a jugar en contra de la Cuadrilateral. Para empezar, la indefinición puede crear errores de percepción, tanto para los propios miembros de la Cuadrilateral como para terceros actores, se opongan estos o no a la iniciativa. En un escenario de dilema de seguridad, como aparenta ser la actual competición con China, las percepciones son el elemento clave. Además, no solo Pequín, sino otros gobiernos y opiniones públicas, tanto nacionales como regionales, podrían malinterpretar (para bien o para mal) la verdadera naturaleza de la Cuadrilateral y lo que esta pretende conseguir. La concreción, sin llegar a constreñir el dinamismo que permite la fórmula de la asociación estratégica, parece perfilarse como la mejor alternativa.

Orígenes y cronología

De cara a comprender mejor la razón de ser de la iniciativa de la Cuadrilateral, será necesario efectuar un breve recorrido por su trayectoria. De esta manera, las posiciones de los distintos países implicados y sus intereses podrán ser puestos en escena sin caer en simplificaciones.

Ya se ha establecido que el Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad consiste en una alianza informal que responde a la fórmula de asociación estratégica. Entre otras cosas, esto implica que el nivel de compromiso de sus miembros es relativamente flexible. En cierta medida, esta fue una de las características que propició su desmantelamiento.

Pero, como muchas otras cosas, no empezó siendo así. Sus orígenes, en su etapa más tentativa, se remontan a las operaciones conjuntas en el contexto del tsunami que arrasó las costas del océano Índico en diciembre de 2004. Durante las operaciones de rescate, Australia, Japón, India y Estados Unidos conformaron el core group de la respuesta coordinada a esta catástrofe natural. El éxito de las operaciones de ayuda humanitaria y la gran compatibilidad que demostraron estos cuatro países durante el desarrollo de las mismas fueron la base sobre la que, en 2007, se construiría el concepto del primer Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad.

Efectivamente, fue tres años después cuando Shinzô Abe, por entonces primer ministro japonés, anunció la formación de un mecanismo de diálogo entre esos mismos cuatro países. En el encuentro que tuvo lugar en Manila, Filipinas, durante el Foro Regional de la ASEAN, se produjeron las primeras conversaciones informales de los cuatro participantes. Sin embargo, India y Australia negaron posteriormente que dichas conversaciones hubieran tenido como tema la seguridad en la región. Aquí se hizo notar, de nuevo, la preocupación ante las percepciones por parte de China.

Con todo, la iniciativa continuó su desarrollo. En septiembre del mismo año se celebraron los conocidos Ejercicios Malabar, los segundos de aquella temporada (Malabar 07-02), unas maniobras militares conjuntas entre Estados Unidos e India. Sin embargo, en aquella ocasión se incluyó a Japón (que ya había participado con anterioridad), Australia y Singapur[2]. De esta forma, los cinco países llevaron a cabo una serie de ejercicios militares en la bahía de Bengala, que incluyeron, entre otros, intercambios de personal, simulacros de control marítimo y operaciones de transporte[3]. A pesar del éxito de las maniobras, la dimisión de Abe y las presiones ejercidas por parte del gobierno chino dieron lugar, poco después, al desmantelamiento de la iniciativa. La retirada de Australia en 2008 fue el hito definitivo que puso fin a la primera vida del Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad.

Habría que esperar a 2017 para presenciar la reavivación de la Cuadrilateral. Llamada de manera informal la “Cuadrilateral 2.0” o “Cuadrilateral vol. 2”, la iniciativa ha vuelto al panorama estratégico regional tras casi una década de creciente inestabilidad y competición entre los distintos poderes presentes en el Indo-Pacífico. A pesar de que no se llevó a cabo ningún esfuerzo relacionado con el Diálogo durante los años que pasó inactivo, sí que se produjo un importante trabajo a la hora de reforzar los vínculos bilaterales que antes habían constituido una de las principales debilidades del mismo. En este sentido, se puede afirmar que los integrantes de la Cuadrilateral se encuentran en un punto de mayor convergencia estratégica que en el pasado, lo que podría facilitar un mejor funcionamiento y, tal vez a largo plazo, la consolidación de la iniciativa.

En 2017 tuvieron lugar numerosos sucesos que marcaron el camino para una nueva y más dinámica Cuadrilateral. Quizás uno de los más relevantes fuera el acuerdo de cooperación nuclear civil entre Japón e India en el mes de junio, que permitirá la exportación de material y tecnología nuclear para su explotación con fines no militares[4]. Este fue un primer paso para la normalización de las relaciones bilaterales, ya que las capacidades nucleares del gobierno indio constituyen un importante factor de su política exterior.

Sin lugar a duda, 2017 fue un año clave para la reactivación de la Cuadrilateral. En septiembre, la visita del primer ministro japonés a India tuvo como objetivo alinear la estrategia nipona del “Indo-Pacífico libre y abierto” con la Act East Policy india, profundizar en la relación bilateral de defensa y, en términos más generales, desarrollar un vínculo más fuerte entre ambos países[5]. En el mes de noviembre, el ministro de asuntos exteriores, Tarô Kôno (actual ministro de defensa) volvió a centrar la atención en el Diálogo Cuadrilateral durante una entrevista, resaltando la necesidad de reavivar esta iniciativa[6]. Y, con reminiscencias del año 2007, los cuatro implicados volvieron a reunirse en Manila para discutir cuestiones concernientes a la seguridad de la región[7]. A partir de este momento, las conversaciones a nivel ministerial bajo la fórmula 2+2[8] se reanudaron y continúan de manera más o menos regular[9].

¿Por qué fracasó en el pasado?

Esta es, quizás, la pregunta más relevante que hay que hacerse para llegar a saber qué se puede esperar en el futuro de la Cuadrilateral. ¿Qué fue lo que hizo que se abandonara la iniciativa? ¿Se han corregido los rasgos y tendencias que la hicieron fracasar? ¿Volverá a suceder algo semejante en los próximos años?

Uno de los principales puntos de divergencia entre los miembros de la iniciativa fue la percepción sobre la amenaza que China representaba para sus intereses. Estados Unidos era el principal interesado en defender su presencia en la región, que el gobierno de Pequín quería a toda costa reducir, tildándola de intervencionista. Las estrategias de la Línea de Nueve Puntos en el mar Meridional y el Collar de Perlas en el océano Índico están diseñadas para garantizar la presencia de China más allá de sus aguas territoriales, y así poder proteger sus intereses comerciales y energéticos en una región muy amplia. Sin embargo, la construcción de infraestructuras (puertos comerciales, bases militares…) asociadas a estas estrategias ponen en riesgo el acceso libre a las importantes rutas comerciales que conectan el golfo de Adén con el este de Asia; al menos, desde la perspectiva estadounidense.

Japón, por su parte, supo aprovechar la creciente inseguridad regional para labrarse un papel como promotor del orden internacional basado en el respeto a las normativas internacionales y al statu quo. Desde hace décadas, la particular situación de sus fuerzas armadas hace que su seguridad dependa, en gran medida, tanto de la actuación de sus aliados como de la estabilidad de su entorno. Desde el punto de vista de la política nacional japonesa, la creciente incertidumbre era el entorno adecuado para promover una reforma constitucional y tener un ejército propio. En el contexto internacional, se posicionaba en defensa de los valores liberales.

Si bien Washington y Tokio eran, como ya se ha explicado, los principales valedores de la iniciativa de la Cuadrilateral, las otras dos partes de la ecuación estaban mucho menos comprometidas con el futuro de la misma.

En el momento de tener lugar las conversaciones iniciales sobre el Diálogo Cuadrilateral, India tenía una posición en política exterior muy distinta a la actual. La problemática relación con Paquistán constituía uno de los más eminentes temas de la política exterior. Por otra parte, los acuciantes problemas sociales que caracterizan al país y las contingencias locales hacían que la mirada del gobierno se dirigiera, sobre todo, hacia el interior de sus fronteras. No fue hasta más recientemente que la doctrina del unilateralismo positivo comenzó a asentarse en el pensamiento estratégico indio. Esta doctrina hace referencia a la idea de que India no podrá defender una instancia como potencia internacional sin estabilizar primero su entorno, es decir, mejorar la relación con sus vecinos, lo que incluye (aunque no se limita a) Paquistán.

Con todo, antes de que India comenzara a aplicar efectivamente este cambio de postura, su acercamiento a la iniciativa de la Cuadrilateral fue muy tentativo. De hecho, tras la cumbre que tuvo lugar en agoto de 2007 en el seno del Foro Regional de la ASEAN (Asociación de Naciones del Sudeste Asiático), durante la cual tuvieron lugar conversaciones paralelas entre Estados Unidos, India, Japón y Australia, tanto los representantes indios como los australianos negaron que se hubieran discutido cuestiones relacionadas con la seguridad y posturas comunes al respecto. En este episodio se manifestó, como en otros similares, la gran preocupación que causaba alterar las percepciones de China sobre las intenciones de una posible colaboración militar.

Finalmente, el hecho que propició de manera más directa el desmantelamiento de la iniciativa fue la retirada de Australia. En el 2008, con la llegada de Kevin Rudd al puesto de primer ministro australiano, se anunció la retirada oficial del país de todas las negociaciones relativas a la Cuadrilateral. Esto provocó, a su vez, la posterior retirada de India, con lo que la iniciativa quedó virtualmente anulada. Se produjeron contundentes especulaciones acerca de supuestas presiones chinas sobre el nuevo gobierno para que se retirase del Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad, pero, tuvieran estas lugar o no, lo cierto es que la credibilidad de Australia a nivel internacional se vio afectada. En concreto, el aparato burocrático de Nueva Delhi parece continuar, a día de hoy, recelosa del verdadero nivel de compromiso por parte de Australia[10].

Equiparar el Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad a un ejercicio de contención en contra de China sería no solo caer en una simplificación terminológica, sino malinterpretar tanto el contexto internacional como las capacidades de los actores implicados. La contención es, simple y llanamente, una opción no viable[11]. El principal razonamiento detrás de esta afirmación se basa en que las medidas necesarias para llevar a cabo una contención efectiva son manifiestamente costosas (por no hablar del riesgo implícito que conllevan) y no se corresponden con las iniciativas que se han tratado de poner en marcha en el marco de la Cuadrilateral. Si se comparase de manera licenciosa esta idea con la contención soviética que llevó a cabo Estados Unidos en el contexto de la guerra fría, se podría observar que este paralelismo no se corresponde con la realidad de lo que sucede en la actualidad. El contexto internacional no es el mismo que en la época de la hegemonía de las superpotencias.

De hecho, la predominancia del elemento militar fue una de las razones que esgrimió Australia para mostrar su recelo sobre la naturaleza de la asociación. Entre los críticos de la iniciativa, además, destacan las voces que argumentan que un enfoque exclusivamente militar no es la mejor alternativa para enfrentarse a los numerosos desafíos regionales. Incluso entre los defensores de la Cuadrilateral hay quienes reconocen estas críticas y argumentan a favor de la postura de que esta asociación debería tomar forma de foro, en el que predominaran las iniciativas económicas y culturales, más allá de un marco meramente geoestratégico y securitario.

Desde que se esbozó por primera vez, la posible construcción del Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad como institución internacional ha pasado por distintos estadios de evolución, cada uno con diferentes niveles de compromiso. En conjunto, el proceso se ha caracterizado por los altibajos y las inconstancias, marcadas por la variable implicación de los gobiernos que descartaban o reintroducían el tema en sus agendas según beneficiase a su propia agenda. Este ha sido, sin descartar otros, uno de los principales impedimentos a que la Cuadrilateral pudiera realmente tomar forma, y tal vez definir sus objetivos con mayor concreción para poder diseñar estructuras adecuadas para llevarlos a cabo.

Cómo se encuadra en el contexto del Indo-Pacífico

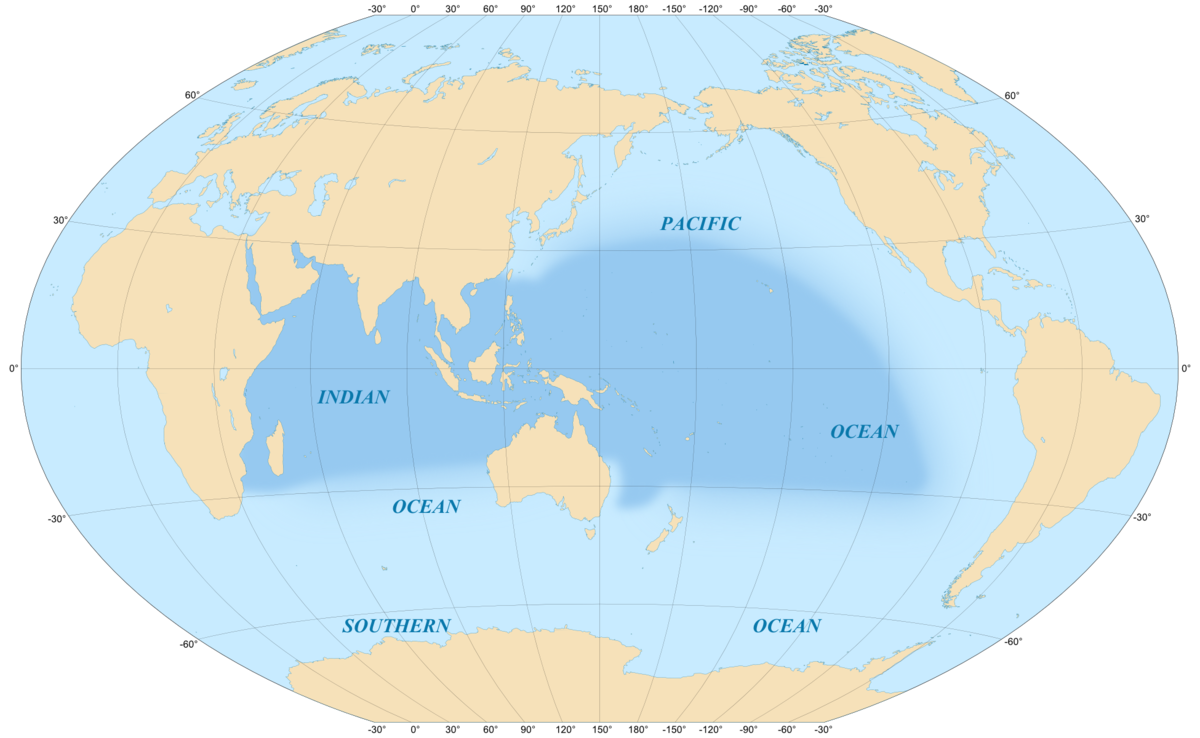

El concepto estratégico del Indo-Pacífico está indudablemente ligado a la concepción del Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad. Es por ello que, en ocasiones, pueden llegar a confundirse[12], aunque en realidad son ideas de muy diversa naturaleza y bien diferenciadas. La expansión del tablero de juego para dar cabida a nuevos actores, como India, forma parte de una gran estrategia de arquitectura regional.

En este contexto, los integrantes de la iniciativa proponen toda una serie de principios de conducta vinculados a esta nueva concepción del Indo-Pacífico como concepto de referencia. Entre dichos principios se cuentan la libertad de navegación y vuelo, el respeto al sistema normativo internacional y al imperio de la ley, y el recurso al arreglo pacífico de controversias. Además, destacan ciertas materias en las que las partes de la Cuadrilateral tienen especial interés en cooperar, como las iniciativas de contraterrorismo, la problemática de la proliferación nuclear, y mejorar la conectividad a nivel regional.

Como concepto estratégico, el Indo-Pacífico es una idea eminentemente marítima. De hecho, el término “indo” hace referencia al océano Índico, y no a India, una malinterpretación bastante habitual. De esta manera, los océanos del Índico y el Pacífico quedan unidos en un único tablero de competición, que posibilita la aparición de nuevos actores y dinámicas internacionales, integrando muy distintos intereses. Así, Japón busca el apoyo de otros actores regionales que tengan la capacidad suficiente para alcanzar los objetivos propuestos, que se concretan en la idea de un “Indo-Pacífico libre y abierto”.

En este nuevo escenario estratégico, India se encuadra como uno de los actores principales. La posición de este país en el panorama regional y sus intereses nacionales respecto a esta cuestión se analizarán más adelante y con mayor detalle. Por ahora, sin embargo, cabe decir que el gobierno de Narendra Modi busca promover toda una serie de iniciativas (relacionadas con la seguridad, pero también más allá de este campo) destinadas a reclamar un puesto de mayor relevancia para su país en el contexto internacional.

India se viene perfilando como la principal potencia con capacidad marítima suficiente para contrarrestar la influencia china en el océano Índico. La estrategia china del Collar de Perlas, que hasta hace pocos años no chocaba en gran medida con los objetivos de la limitada política exterior india, se interpreta cada vez más desde la perspectiva de la competición estratégica. Por poner un ejemplo, la importante inversión en infraestructuras que China ha destinado al puerto de Gwadar, en Paquistán, resulta especialmente preocupante para Nueva Delhi.

Una de las características más definitorias del Indo-Pacífico como región es su indudable vinculación a los flujos económicos internacionales. Desde el golfo de Adén hasta Japón, estas aguas son el lugar de paso de grandes autopistas oceánicas (sea lanes) que mueven el mayor porcentaje del comercio marítimo del mundo. Estas grandes rutas comerciales oceánicas constituyen un factor estratégico de gran importancia, puesto que transportan, entre un sinfín de mercancías, toneladas de hidrocarburos que se distribuyen por toda Asia. Si se tiene en cuenta que países como China, Corea del Sur, Taiwán o Japón son grandísimos importadores de recursos energéticos, la relevancia de estas redes comerciales queda establecida. La capacidad para tener acceso libre a estos recursos es un requisito necesario para las respectivas seguridades nacionales de los países de la región.

El sudeste asiático es un área eminentemente insular. La compleja geografía de esta área hace que se formen cuellos de botella[13] naturales que dificultan la navegación y los flujos comerciales. Esto ha dado lugar a lo que se ha pasado a denominar el “dilema de Malaca”[14]. Un hipotético bloqueo de estos puntos estratégicos por parte de las fuerzas armadas de un país competidor podría poner en jaque la economía de uno de los ya citados gobiernos al jugar la carta de la dependencia energética. Los estrechos de Malaca, Sunda y Lombok son los más transitados, lo que los señalaría como los objetivos más probables en este caso imaginario. Toda el área comprendida entre Darwin (Australia) y Singapur constituye un gran embotellamiento comercial en el que proliferan los puntos de congestión.

Al margen del enfoque geoestratégico, hay que tener también en cuenta otro tipo de riesgos que presentan estos puntos, como la proliferación de la piratería y la presencia de organizaciones criminales transnacionales que llevan a cabo actividades como el tráfico humano, de armas o de narcóticos. Cualquiera de estos actos constituye una amenaza severa para la seguridad nacional y los intereses de los países afectados. Por ejemplo, solo la pesca ilegal constituye un gran riesgo para una economía como la de Indonesia y otros pequeños Estados insulares; por no hablar de su potencial vinculación a otro tipo de actividades ilícitas[15]. La cooperación entre las partes interesadas para acabar con esta clase de comportamientos y garantizar la seguridad en estas aguas más allá de grandes pactos de poder es no solo necesario, sino que se podría articular como uno de los pilares de la construcción de instituciones a nivel regional. Un esfuerzo que interesase a jugadores de tamaño medio y pequeño de cara a integrarse en iniciativas más ambiciosas, pero que tuviera en cuenta sus intereses y necesidades.

Análisis de las posturas de los distintos países

Como ya se ha señalado con anterioridad, para que la iniciativa salga adelante es necesario que las percepciones e intereses de los miembros se alineen de manera adecuada. Con todo, la cuestión sobre la verdadera naturaleza de estos intereses no ha sido resuelta. Sigue siendo imperante trabajar este punto más allá de un simple código de valores compartidos, por mucho que este sea el elemento central de unión en una etapa relativamente “temprana”, en la que la indefinición no da pie a compromisos más contundentes. Teniendo esto en cuenta, es necesario hablar, también, de si realmente dichas aspiraciones e intereses coinciden o no. En páginas anteriores ya se ha discutido que esta falta de alineación fue uno de los errores que llevó al desmantelamiento de la Cuadrilateral en 2008. Por lo tanto, la pregunta pertinente es: ¿qué ha cambiado a este respecto?

China es el elemento central de las percepciones de inestabilidad entre los miembros de la Cuadrilateral, pero también lo es de sus diferentes aproximaciones a la cuestión. No solo Australia, como ya se ha visto, tiene dificultades a la hora de compaginar su relación con Pequín y sus intereses securitarios. Japón, sin ir más lejos, protagonizó un período de acercamiento al gobierno chino tras el desmantelamiento del Diálogo Cuadrilateral[16]. Sin embargo, esta línea de actuación parece no haber sido satisfactoria para el gobierno nipón.

Parece ser que la Cuadrilateral 2.0 vendrá motivada por las ambiciones regionales de India y Japón, que buscan aumentar su influencia a la vez que defienden el statu quo. Australia, por su parte, buscará diversificar y profundizar sus alianzas con otros poderes de la región, más allá de China y las alianzas tradicionales con Estados Unidos, país que se considera inestable debido al liderazgo del presidente Donald Trump[17].

Japón

Para comprender las dinámicas de la cuestión, analizar las posturas individuales de los países implicados en el Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad es imprescindible.

Japón siempre ha sido el principal valedor de la iniciativa de la Cuadrilateral. Esto es debido, en parte, a las percepciones negativas que el país tiene sobre la seguridad de su entorno. No solo la asertividad de China en el ámbito marítimo regional, sino también la impredecibilidad de Corea del Norte como actor revisionista al margen de la comunidad internacional.

Para Tokio, la Cuadrilateral representa una oportunidad única por muy diversos motivos. En primer lugar, sería una herramienta adecuada para establecer cierta competición de cara a la presencia china en el mar Meridional y el resto del Pacífico occidental. Preocupa especialmente la situación respecto a la soberanía de las Islas Senkaku (llamadas Diaoyu en chino), en disputa desde hace varias décadas, y las incursiones territoriales en las aguas de la prefectura de Okinawa, en el mar del Este. La medida más llamativa tomada al respecto de estas “situaciones de zona gris”[18] ha sido la de la constitución de una cadena defensiva de islas, conocidas como el “muro sudoeste”, en las que se pretende instalar sendos sistemas de defensa para defender el territorio japonés de una posible incursión.

Las Fuerzas de Autodefensa (FAD), que sustituyen en cierto modo a unas fuerzas armadas regulares, han experimentado grandes cambios en la última década. El desarrollo de capacidades marítimas y anfibias ha sido una de las principales prioridades del ministerio de defensa, diseñadas, sin duda, para contrarrestar las cada vez más frecuentes “situaciones de zona gris” presentes en el entorno de seguridad japonés.

Sin embargo, en el amplio entorno regional, Japón no puede valerse de sus propios medios para contrarrestar a Pequín, puesto que la propia constitución del país renuncia a la guerra y a tener un ejército propio. Esta disposición queda recogida en el polémico artículo 9, principal objetivo de las corrientes revisionistas en Japón.

(Continúa…) Estimado lector, este artículo es exclusivo para usuarios de pago. Si desea acceder al texto completo, puede suscribirse a Revista Ejércitos aprovechando nuestra oferta para nuevos suscriptores a través del siguiente enlace.

IMPORTANTE: Las opiniones recogidas en los artículos pertenecen única y exclusivamente al autor y no son en modo alguna representativas de la posición de Ejércitos – Revista digital sobre Defensa, Armamento y Fuerzas Armadas, un medio que está abierto a todo tipo de sensibilidades y criterios, que nace para fomentar el debate sobre Defensa y que siempre está dispuesto a dar cabida a nuevos puntos de vista siempre que estén bien argumentados y cumplan con nuestros requisitos editoriales.

Be the first to comment