Por primera vez en casi 50 años hemos asistido al bloqueo del canal de Suez… por el encallamiento de un buque portacontenedores gigante. Tras seis días bloqueando esta ruta vital para el comercio, el portacontenedores fue finalmente liberado. El comercio global, nuestras economías son muy dependientes de la navegación. En estos últimos días esta dependencia ha sido más evidente que nunca. En este artículo vamos a analizar las razones del bloqueo del canal de Suez y a intentar responder algunas preguntas clave que responderemos a lo largo de este artículo: ¿Estamos ante un incidente aislado o ante una señal de lo que está por venir? ¿Se ha quedado el canal de Suez anticuado? ¿El bloqueo del canal de Suez será el fin para los grandes barcos? A pesar de la presencia de piratas, ¿deberíamos tener en cuenta rutas alternativas como la del cabo de Buena Esperanza? ¿Será alguna vez la ruta del Ártico una alternativa viable?

Amazon, Ali Express… casi todo lo que compra por Internet ha viajado por mar.

Las personas que investigamos la seguridad del transporte marítimo insistimos con frecuencia en el dato de que el 90% del comercio se mueve por mar. Y eso supone que la economía global depende de que no haya problemas en esas rutas marítimas que se pueden intuir en la siguiente imagen y pueden ver en este vídeo:

El vídeo ha sido realizado por Marine Traffic, una aplicación que rastrea los barcos, gracias al sistema de identificación automática, que es algo así como el GPS que tienen obligación de llevar encendido la mayoría de los buques.

El vídeo está realizado a tiempo real en los meses de septiembre y octubre de 2015. Rastrea tres tipos de buques: en amarillo los portacontenedores, es decir, esos buques de hasta 400 metros de largo, el equivalente a cuatro campos de fútbol, y que llevan más de 20.000 contenedores a bordo; contenedores que luego vemos en los trenes, en los camiones y que permiten que lleguen los productos hasta nuestras tiendas y hogares. En verde aparecen los cargueros y en rojo los petroleros. Cuanto más intenso es el color más tráfico de buques se produce en un área determinada.

Si observamos el vídeo, es fácil distinguir en rojo la presencia de petroleros en el golfo de México y en Venezuela. También el tráfico intenso en el río de la Plata en Argentina. Y en Brasil, en los puertos de Santos y de Río de Janeiro. El golfo de Guinea es también una zona crítica de extracción de hidrocarburos y por eso vemos tantas líneas en rojo. Sin ir más lejos el año pasado el 20% del crudo que llegó a España vino de Nigeria, que es nuestro principal proveedor. Es, pues, una zona estratégica para España y también para Europa. A continuación, el vídeo nos conduce al viejo continente: ahí ven el tráfico en Gibraltar, el fuerte impacto de los puertos del centro de Europa (Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Hamburgo), incluso se puede seguir el tráfico fluvial por el Rin y por el Danubio. Después, los estrechos de Dardanelos y del Bósforo, el canal de Suez, el golfo Pérsico (de nuevo esas líneas rojas de petroleros). Y, cómo no, el enorme tráfico de portacontenedores en los puertos chinos: en poco más de 10 años China ha pasado de tener 3 puertos en la lista de los 10 más importantes por tráfico de portacontenedores a tener 7. Esa imagen brillante demuestra su pujanza como país exportador. Y, por último, vemos el estrecho de Malacca, un área crítica para las economías de China, Japón o Australia.

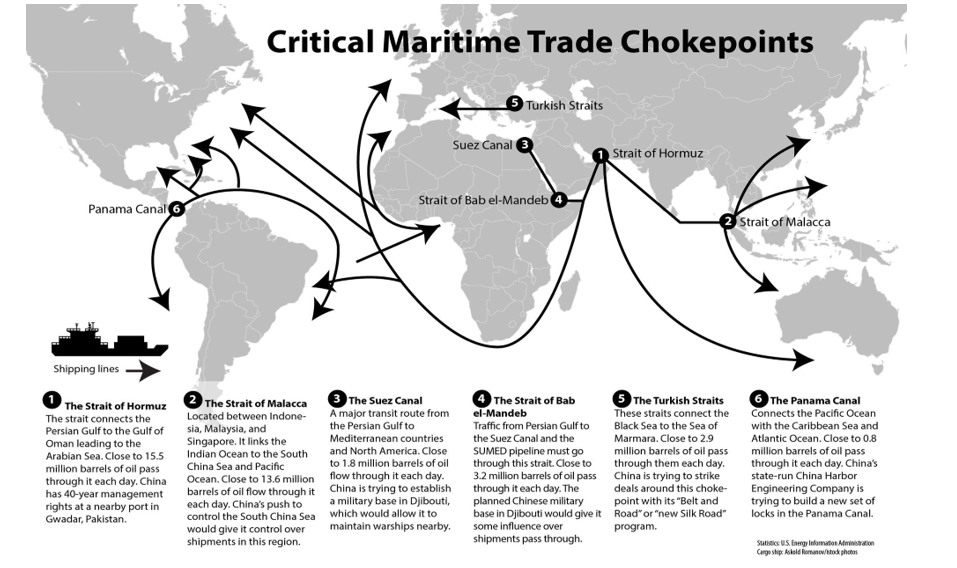

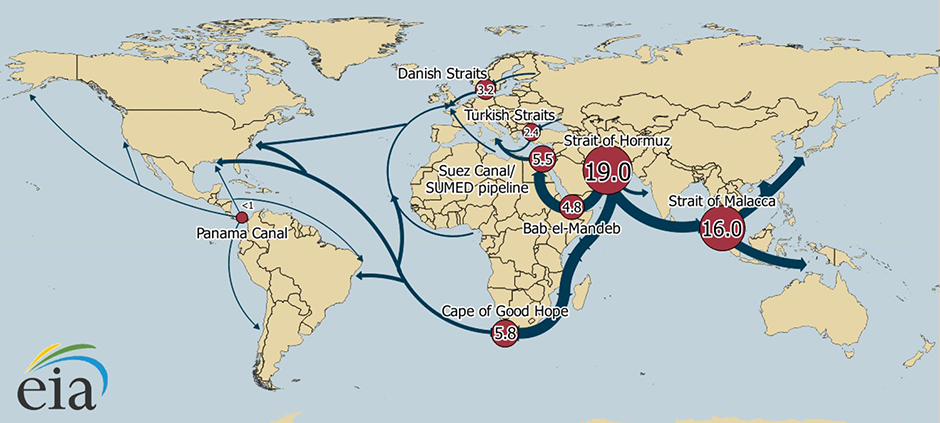

No es difícil visualizar en el mapa los denominados cuellos de botella o puntos de estrangulamiento, esas zonas de tráfico denso en áreas geográficas estrechas, y que son puntos críticos para el comercio marítimo. Algunos son creados por el ser humano (canales de Panamá y Suez) y otros se explican por su situación geográfica (estrechos de Dardanelos y Bósforo, Bab el Mandeb, Ormuz o Malacca).

Un ejemplo de la dependencia de nuestras economías del tráfico marítimo lo tienen en la siguiente imagen. De los aproximadamente 57 millones de barriles de petróleo que se mueven cada día por mar, el 33% depende de que no haya problemas para la navegación en Ormuz y otro 28% de que la ruta esté despejada en Malaca.

Con este vídeo y estas imágenes Vds. ya se habrán hecho una idea de qué supone el bloqueo del canal de Suez o de cualquiera otra de una de esas rutas marítimas. No shipping, no shopping. Pues justo eso es lo que ocurrió el pasado mes de marzo en pleno canal de Suez, por donde transcurre el 12% del comercio marítimo. Un enorme buque portacontenedores se cruzó en el canal y bloqueó el paso a cualquier mercante. Cientos de ellos se agolparon a ambos extremos de la infraestructura.

Es cierto que un caso como este es realmente raro. De hecho, el bloqueo del canal de Suez sólo se había vivido en dos ocasiones desde su inauguración oficial, allá por 1869. Y en ambos casos por sendos conflictos bélicos: la Guerra del Sinaí en 1956 y la Guerra de los Seis Días en 1967. En la primera ocasión el origen fue precisamente la nacionalización del canal por el presidente egipcio Nasser, conflicto que impidió la navegación durante varios meses. En el segundo caso el conflicto se desató entre Israel y una coalición árabe y obligó a cerrar el canal nada menos que ocho años, hasta 1975. Su reapertura sería parte del acuerdo que puso fin a la guerra del Yom Kipur (o del Ramadán o guerra árabe-israelí) de 1973.

Pero volvamos al presente para intentar entender cómo se produjo el accidente y qué preguntas que se han planteado en los medios en las últimas semanas se pueden responder a día de hoy.

¿Por qué encalló el buque?

La mayoría de este tipo de accidentes en el transporte marítimo tiene en su origen un fallo humano. En el caso del mercante protagonista de esta historia, el Ever Given, parece que unas condiciones climáticas complicadas, con viento especialmente fuerte (40 nudos) y una tormenta de polvo, pudieron impedir una buena visibilidad y provocar que el portacontenedores acabara ladeándose hasta encallar.

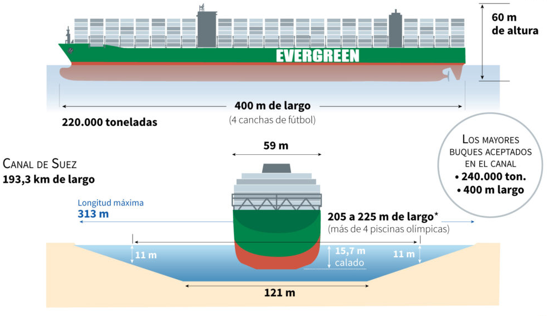

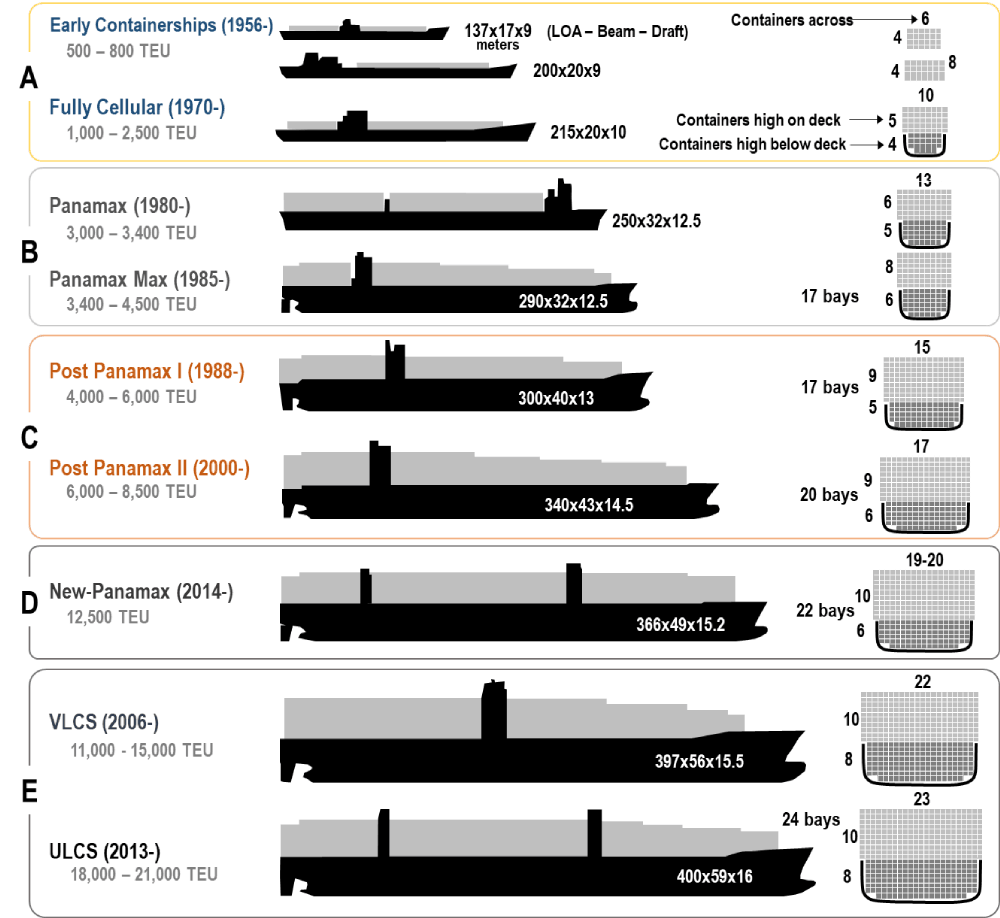

Este buque es uno de los más grandes portacontenedores que navegan hoy por los mares y océanos de nuestro planeta. 400 metros de eslora (de largo), 59 metros de manga (anchura), 60 metros de altura… puede transportar unos 20.000 contenedores. En este tipo de navegación por Suez estos buques no suelen ir solos sino con remolcadores y prácticos con amplia experiencia. Sin embargo, por lo que sabemos parece que en esta ocasión no se utilizaron remolcadores durante la travesía.

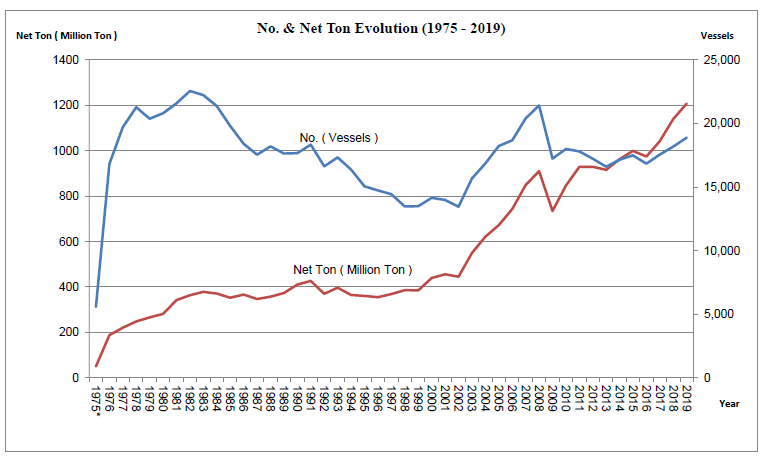

En las últimas décadas la capacidad de estos gigantes flotantes no ha hecho sino aumentar. Si en las décadas de 1950 y 1960 apenas podían almacenar un millar de contenedores, los últimos modelos, como el HMM Algeciras, construido en Corea del Sur, navega desde abril de 2020 con una capacidad máxima de 23.964 contenedores y 61 metros de manga. Pero, ¿por qué se usan mercantes cada vez más grandes? Por economía de escala: cuanto más grande es el buque más eficiente es el transporte de mercancías. Usar un buque que embarca 20.000 contenedores en vez de dos de 10.000 contenedores cada uno supone ahorrar combustible, reducir el coste por contenedor así como la contaminación. Un ejemplo del propio canal de Suez: en el año 2011 lo atravesaron 7.179 portacontendores, mientras que en 2018 lo hicieron 5.706, es decir, un 20% menos. Sin embargo, el tonelaje que de media llevaron esos buques se incrementó entre ambas fechas en casi un 53% (Bereza, Rosen y Shenkar, 2020).

Así pues, los portacontenedores son cada vez más grandes y esto complica su paso por ciertas áreas. De hecho, hay muy pocos puertos en el mundo que los puedan alojar. El Ever Given pesa 220.000 toneladas y su calado es de 14,5 metros. Por lo tanto, no debería haber tenido problema para cruzar Suez, que permite el paso de barcos de hasta 20 metros de calado y 240.000 toneladas. Pero, evidentemente, un tamaño mayor implica un mayor riesgo, como se ha demostrado. De hecho, no es infrecuente que estos enormes buques pierdan algunos contenedores cuando son azotados en mar abierto por fuertes tormentas.

Pero, ¿no se había ampliado el canal de Suez? ¿Ya se ha quedado obsoleta esta obra?

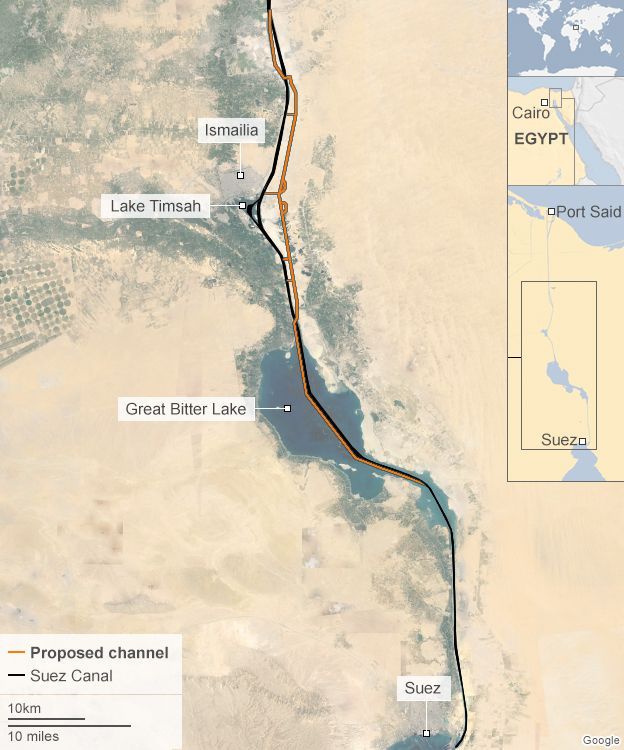

En efecto, el 6 de agosto de 2015 se inauguró el nuevo canal de Suez después de un año de trabajos intensos y unos 8.000 millones de dólares de inversión. Con la nueva infraestructura se confiaba en duplicar el número de buques que podían atravesar el canal cada día, llegando hasta unos cien mercantes. La obra recordaba a las grandes infraestructuras puestas en marcha por el fundador del Egipto moderno, el presidente Nasser. Hacía décadas que el país no se embarcaba en un proyecto con un simbolismo tan fuerte y liderado por el Ejército. Y la nueva obra también permitió al presidente egipcio, Al Sisi, que había llegado al poder mediante un golpe militar dos años antes, reafirmar un discurso nacionalista para fortalecer su imagen interna.

Según se anunciaba entonces, el nuevo canal reduciría el tiempo necesario para cruzarlo casi a la mitad (de unas 20 horas a 11 horas) haciéndolo más competitivo comparado con su homólogo panameño (18 horas).

Para entonces Egipto ingresaba unos 5.000 millones de dólares anuales gracias al canal. La previsión del Gobierno egipcio era que, con la nueva ampliación, en 2023 los ingresos superarían los 13.000 millones de dólares por año. Sin embargo, 2020 acabó con unos ingresos por derechos de tránsito del canal de 5.610 millones de dólares, un 3,3% menos que en 2019. Y el número de buques que lo atravesó en 2020 fue de 18.829, cifra muy similar a la del año anterior, es decir, una media de 51 mercantes por día. El transporte marítimo, muy dependiente de la evolución económica global, se ha visto afectado también por la crisis generada por la pandemia del coronavirus, lo que ha repercutido en los beneficios del canal.

Pero es que, además, debemos tener en cuenta que la parte del canal que se amplió en 2015, y que permitió crear una vía paralela a la entonces existente, se encuentra al norte del lugar donde encalló el Ever Given, más próximo a Suez. Por lo tanto, dicha ampliación no afectó al área donde se produjo el incidente. No se ha quedado, pues, obsoleto el canal.

Sin embargo, tras el accidente, el responsable de la Autoridad del Canal de Suez, Osama Rabie, señaló que no renuncia a una ampliación del tramo sur, justo en el área donde se bloqueó el buque, desde los 250 metros actuales a 400 metros de anchura así como a adquirir grúas que puedan descargar a una altura de 52 metros (Ebrahim y Werr, 2021).

Lo que parece claro, como veremos a continuación, es que Egipto difícilmente va a poder aprovechar las hipotéticas indemnización para sufragar ninguna obra.

¿Quién pagará el coste de tener parado el canal durante seis días? ¿Y los retrasos en las entregas?

Las facturas a pagar por el bloqueo del canal de Suez por el Ever Given serán numerosas. Lloyd´s List calculó unas pérdidas de 400 millones de dólares por hora para el comercio global (Teoh, 2021). Sin embargo, no será fácil delimitar la responsabilidad. Diversos bufetes de abogados ya señalan que el elemento clave será la causa del incidente: error humano, fallo mecánico o fuerza mayor. No parece sencillo alegar las condiciones meteorológicas como fuerza mayor en estos buques. Más bien, se prevé que la responsabilidad recaiga en el armador y/o los prácticos a bordo del buque. Los seguros, por su parte, cubrirán los daños al barco y a su carga o los que el mercante haya causado en el canal. Algunos analistas consideran que aseguradoras y reaseguradoras deberán abonar más de 100 millones de dólares (Sheehan, 2021). Los gastos por retrasos en la entrega no suelen estar cubiertos por las pólizas (Palau, 2021).

Cabe señalar que los barcos retenidos llegarán tarde a EE. UU. y Europa, lo que generará posteriormente congestión en los puertos de destino, lo cual, a su vez, provocará nuevas demoras, que derivarán en un retraso de su llegada a Asia para cargar nuevos pedidos. Se calcula que más de 400 mercantes quedaron retenidos a ambos extremos durante el bloqueo del canal de Suez. Para resolver esta incidencia que afectará al transporte marítimo durante semanas ya se proponen soluciones como priorizar los envíos urgentes, convertir envíos marítimos en aéreos o remitir de Asia a Europa por ferrocarril parte de la carga prevista para ser embarcada (Pitelli, 2021).

(Continúa…) Estimado lector, este artículo es exclusivo para usuarios de pago. Si desea acceder al texto completo, puede suscribirse a Revista Ejércitos aprovechando nuestra oferta para nuevos suscriptores a través del siguiente enlace.

IMPORTANTE: Las opiniones recogidas en los artículos pertenecen única y exclusivamente al autor y no son en modo alguna representativas de la posición de Ejércitos – Revista digital sobre Defensa, Armamento y Fuerzas Armadas, un medio que está abierto a todo tipo de sensibilidades y criterios, que nace para fomentar el debate sobre Defensa y que siempre está dispuesto a dar cabida a nuevos puntos de vista siempre que estén bien argumentados y cumplan con nuestros requisitos editoriales.

Be the first to comment