Para desatar el nudo del Sahel o, al menos, intentarlo hay que empezar por las viejas rencillas, afrentas y enfrentamientos entre comunidades y, dentro de ellas, entre elites y clases bajas. Vienen de lejos y las acciones de los gobiernos a lo largo del tiempo han desembocado en mayores beneficios para unos (granjeros, sobre todo) y han ido en detrimento de otros (especialmente pastores). A ello se une en la última década el elemento yihadista, que aprovecha este caldo de cultivo para tratar de hacerse con los recursos (poder e influencia) para, entre otros objetivos, negociar con el Gobierno y también lograr adeptos.

Por si lo anterior no fuese suficiente, todo ello está jalonado con ataques y asesinatos para “convencer” de sus “bondades” y de las de su discurso religioso, anticolonial, antifrancés y antisistema. La aparición de los yihadistas en escena implica la intervención extranjera: Francia, UE, EE. UU., UA y el G5 Sahel, con un papel de las fuerzas armadas locales especialmente sangriento y ambiguo con algunas milicias rebeldes. Y, a todo, aún hay que sumar un elemento más: el cambio climático, con lo que supone de agravante, ya que se lucha por unos recursos menguantes.

Sahel: Una década de violencia en aumento

“Hay que actuar para organizar el retorno de los civiles. Mi único sueño es volver a casa. Rezo para que nuestro país recupere la paz que tuvo. La solución es el diálogo. Nosotros deseamos regresar lo antes posible”, es el llamamiento de uno de los 401.736 desplazados internos del conflicto maliense a fecha de septiembre de 2021. Solo en la región de Mopti, la violencia entre febrero de 2020 y septiembre de 2021 ha ocasionado el desplazamiento forzoso de más de 100.000 personas (un total de 159.027). Este testimonio recogido en una entrevista en Bamako en octubre de 2020 y los datos aportados aparecen en el informe recientemente publicado por el Instituto Danés de Estudios Internacionales sobre el conflicto en el Sahel y cuyo análisis es el objeto de este documento.

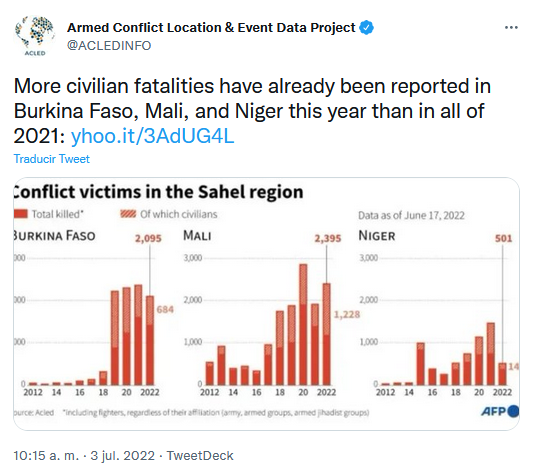

Cientos de miles de desplazados internos que huyen de la escalada de la violencia en el país desde el inicio de la crisis de seguridad en 2012 y que cada vez le cuesta la vida a un mayor número de civiles:

Como se observa en la gráfica que podéis encontrar al final del epígrafe, conforme aumenta la violencia en el Sahel se hace cada vez más imperativo el conocer lo mejor posible quiénes, el por qué se ven envueltos en esa espiral ascendente y cómo se desarrollan las dinámicas que desembocan en violentos enfrentamientos. Pero, también, quiénes la sufren, por supuesto. Todo para intentar, en la medida de lo posible, analizar los errores cometidos y poder atajarla.

Franquicias de grupos yihadistas, milicias locales, bandas criminales, fuerzas de seguridad, ejércitos extranjeros… son los actores que, con diferentes motivos, ideologías y agendas se mueven sobre el terreno persiguiendo sus propios intereses. Y, para ello, en algunas ocasiones recurren a explotar viejas rencillas o injusticias casi ancestrales y, en otras, es justo al contrario, se explotan nuevos problemas creados por nuevas situaciones o circunstancias.

Conflictos preexistentes que se desarrollan a la vez que un proceso imparable hasta el momento de cambio climático. Este factor añadido actúa como acelerante y agravante, pero no desencadenante per se. Según sostiene el informe danés, el vector que genera conflicto es la falta de una acción y gestión eficientes de los recursos naturales en lo que a la tierra y al agua se refiere, sobre todo, al estar cada vez más tensionados por el cambio climático. De este modo, la inseguridad alimentaria se suma a los problemas anteriores políticos y económicos en la zona, disparando la posibilidad del estallido de más enfrentamientos por el acceso y uso de unos recursos menguantes.

Un estudio de caso: la región Mopti en Mali

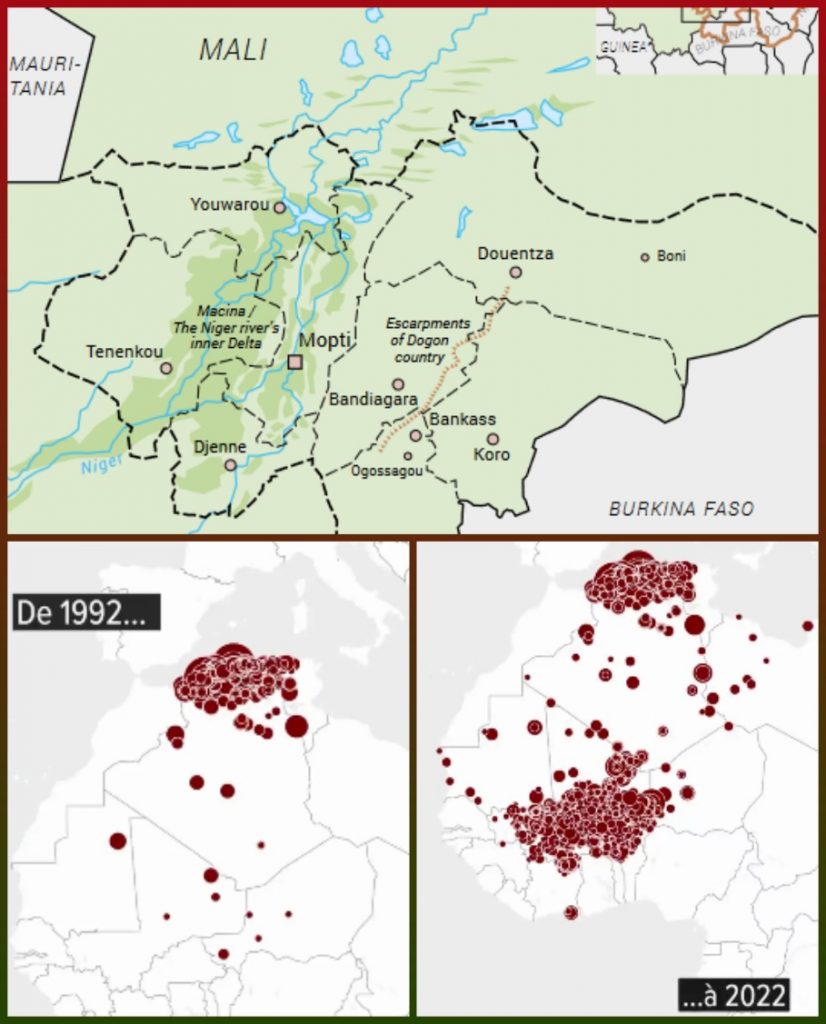

Lo expuesto en párrafos anteriores se ejemplifica en la región central maliense de Mopti, epicentro de la violencia en el país y donde conflicto, escasez de recursos y cambio climático interactúan entre sí de forma compleja.

La gráfica que hemos compartido a continuación sitúa la región de Mopti en el mapa, en el centro de Mali. Mientras abajo se recogen ataques yihadistas en toda la región desde 1992 hasta 2022, observándose claramente con el paso del tiempo el incremento de los mismos en el área en el que se encuentra Mopti y, más allá, el corazón del Sahel.

En Mopti, en concreto, la inseguridad ha supuesto el abandono de las autoridades locales, y estatales, de sus puestos y responsabilidades. Esto a su vez ha derivado en un auge en la zona de la presencia e influencia de diversos grupos armados que se han aprovechado de las disputas entre los habitantes (por el control de la tierra y el agua) y de su falta de protección. Y aún más, la alta disponibilidad de armas ha intensificado la violencia contra los civiles y los ha dejado más expuestos.

No solo yihadistas, sino también bandas criminales, ajustes de cuentas entre comunidades y fuerzas de seguridad interactúan en este caldo de cultivo de enfrentamientos armados. A esto hay que sumar la intervención internacional que ha sentado prioridades domésticas y que, con su apoyo, ha supuesto el retorno brutal de unas fuerzas armadas estatales con lazos ambiguos con las milicias de autodefensa locales y que han agravado la violencia y el clima de impunidad en esta castigada región.

Actores y vectores de conflicto en el Sahel

Acelerada por la caída de Gadafi, la crisis de seguridad de Mali estalla en 2012 cuando una coalición de rebeldes separatistas Tuareg y tres grupos yihadistas (AQIM, MUJAO-Movimiento para la Unificación y la Yihad en África Oeste- y Ansar Dine) toman el control del norte del país y declaran el estado independiente de Azawad.

En poco tiempo, los yihadistas derrotan a los tuaregs y amenazan la capital, lo que conlleva la intervención militar francesa, la Operación Serval, en enero de 2013. Ocupadas con esto, las fuerzas de seguridad malienses se olvidan de las tensiones crecientes en el centro del país entre pastores de etnia Fulani y granjeros Dogon (problemas que en las zonas húmedas incluye también a los pescadores). Unas disputas relacionadas con los derechos de pastoreo, la tierra y el agua que vienen de lejos, agravadas por las sequías, la corrupción de los funcionarios y la marginalización, sobre todo de los pastores Fulani, cuya forma ancestral de vida se ve perjudicada por los beneficios legales hacia los granjeros Dogon.

Ya con esta situación, entran en escena en la región de Mopti los grupos yihadistas, que utilizan estos problemas para afianzarse, ampliar su influencia, acceder a los recursos y reclutar miembros entre los locales. A partir de 2014, con la presión francesa en el norte, estos grupos se mueven hacia el sur, hacia Mopti (como se decía unas líneas más arriba) y las fronteras con Burkina Faso y Níger. A continuación, una infografía con la cronología de la formación de los distintos grupos yihadistas en el marco de la crisis de seguridad de Mali:

De este modo, a partir de 2015 encontramos un aumento significativo de la inseguridad y la violencia en toda el área con grupos yihadistas, fuerzas armadas malienses, la fuerza conjunta regional G5 Sahel y un número cada vez mayor de milicias de autodefensa locales. Estas últimas en un intento de las comunidades por protegerse ante la falta de seguridad y la huida de las autoridades por los ataques yihadistas en este cada vez más violento contexto de grupos enfrentándose unos contra otros y entre sí.

Esto, por supuesto, los que no han entrado directamente a engrosar las filas de las franquicias de Al Qaeda y Dáesh en la región en busca no solo de protección sino, además, en un intento por conseguir mejorar su situación política (ganar influencia) para lograr objetivos económicos. Por ejemplo, en el caso de los pastores Fulani, el recuperar sus derechos de pastoreo frente a los granjeros Dogon. Otros entran por motivos diferentes, como la mejora de su situación social, si hablamos de las clases más bajas, o la nostalgia de otros tiempos antiguos y mejores para sus respectivas etnias o pueblos.

Entre los grupos mencionados en párrafos anteriores destacan algunos por sus capacidades, como:

(Continúa…) Estimado lector, este artículo es exclusivo para usuarios de pago. Si desea acceder al texto completo, puede suscribirse a Revista Ejércitos aprovechando nuestra oferta para nuevos suscriptores a través del siguiente enlace.

IMPORTANTE: Las opiniones recogidas en los artículos pertenecen única y exclusivamente al autor y no son en modo alguna representativas de la posición de Ejércitos – Revista digital sobre Defensa, Armamento y Fuerzas Armadas, un medio que está abierto a todo tipo de sensibilidades y criterios, que nace para fomentar el debate sobre Defensa y que siempre está dispuesto a dar cabida a nuevos puntos de vista siempre que estén bien argumentados y cumplan con nuestros requisitos editoriales.

Be the first to comment