On Wednesday, November 11, 2020, a document was published on the official website of the Russian Government, pending presidential ratification, of utmost importance for Russian foreign strategy. The text included a proposal for an agreement intended for the government of Sudan that, if materialized, would culminate in the opening of a permanent Russian naval base in the Red Sea. It is therefore necessary to analyze the context in which the news occurred, the possible motivations of the Kremlin and the foreseeable consequences of this movement.

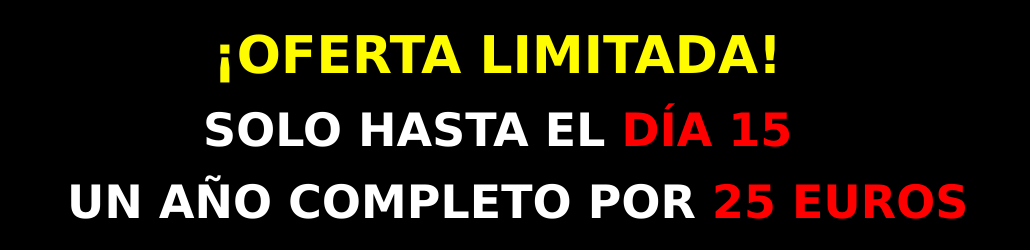

(Keep reading…) Dear reader, this article is exclusively for paying users. If you want access to the full text, you can subscribe to Ejércitos Magazine taking advantage of our offer for new subscribers through the following link.

Be the first to comment