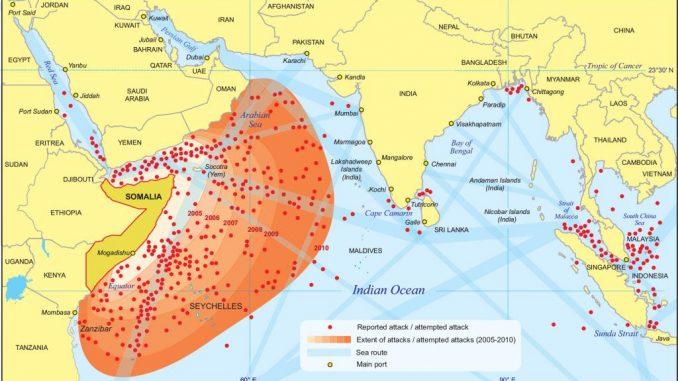

Seven years after Somali pirates managed to capture the last ship that allowed them to collect a ransom, the threat of piracy in the region has not been eliminated, as confirmed by the incidents that occur, although increasingly sporadic. It has therefore been possible to successfully reduce the area in which pirates operate and the severity of the threat, despite which we are far from reaching the moment when the guard can be lowered.

(Keep reading…) Dear reader, this article is exclusively for paying users. If you want access to the full text, you can subscribe to Ejércitos Magazine taking advantage of our offer for new subscribers through the following link.

1 Trackback / Pingback